Le Victorial and the attack on Jersey in 1406

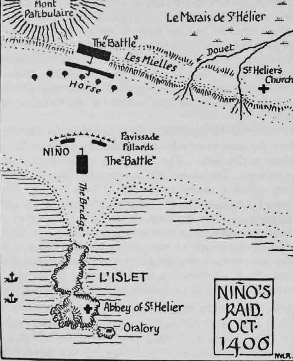

A diagram of the field of battle at West Park

|

Islands coveted by French

It is scarcely necessary to point out the great importance of the possession of the Norman Isles to England, during that part of the Middle Ages, when she held Aquitaine, Gascony and other provinces in the sonth-west of France. These islands then formed a naval base invaluable in time of war, and of immense service for the protection of English commerce, and it is not surprising if the French coveted their possession.

It were to be hoped that some competent student would collect the scattered materials available, and present us with a picture of the part played by the Islanders in the naval warfare between their quarrelsome neighbours.

Speaking generally, historians have been content to class many of the attacks on these islands, as mere acts of piracy, devoid of national import; but if we take the trouble to go to the documentary sources of information, we shall find that the responsibility of the governments was more often than not involved.

Particularly was this the case during the Hundred Years War, when, notwithstanding the frequent truces, a permanent state of war may be said to have existed. These islands were incessantly involved in this mighty struggle and suffered untold hardships from the attacks of the enemy.

'Spanish' attack

It is with one of these episodes that this paper deals; the so-called Spanish attack on Jersey in 1406 by Pero Nino, Count of Buelna. Local historians have been content to make a passing mention of this event, and notwithstanding the first-hand information contained in the Chronicle known as Le Victorial it has generally been represented as traditional. Fortunately, documents, now in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris, prove the general accuracy of the account of the chronicler, and shed new light on this episode, as we shall see later on.

We shall gain a better impression of the picture of the times If we first give some account of the dramatis personae.

The Spanish Chronicle Le Victorial, which celebrates the explcits of Pero Nino, Count of Buelna, was written by Gutiere Diaz de Gamez, his faithful lieutenant and standard-bearer. This work, though merely a biography of the Count, is unique for its brilliant description of the sea-fights, and of the customs and manners of the knightly society of those days.

Le Victorial deserves to rank with the famous Loyal Serviteur of Bayard, and with the Chronicles of Froissart, An admirable translation into French by Le Comte de Circourt and Le Comte de Puymaigre, published in 1867 in Paris, is available for those who wish to make the acquaintance of its thrilling and at times amusing pages.

Born about 1378, Pero Nino came of noble stock, and received his education at the Court of Castile, where he held the post of gentleman in attendance on the Infante Don Henry. Trained in the profession of arms, be was commissioned in 1403, at 25 years of age, to attack the Barbary Corsairs in the Mediterranean.

Franco-Spanish alliance

Ever since de Guesclin had deposed Pedro the Cruel, and placed Henry of Transtamare upon the throne of Castile, the alliance between that power and France, remained a political tradition, and in the opening years of the 15th century, Charles VI, at war with England, sought its help.

The Great Armada of Seville was directed to co-operate with the French fleet, and Nino succeeded in obtaining the command of a squadron of three galleys. The Armada apparently did little else than act as convoy to merchant ships, and Nino, tired of this life of inaction, broke away and sought adventure on his own account with his three little vessels, and was accompanied hy his faithful standard-bearer and biographer, Gutiere de Gamez.

Nino was a redoubtable sea captain. He sailed up the Gironde, burning and pillaging Bordeaux, and went off with his booty to La Rochelle. There he met Messire Charles de Savoisy, another sailor of renown, and they combined their fleets for a cruise in the English Channel. During the summer of 1405 they raided the south coast of England, taking a town in Cornwall, laying Portsmouth under contribution, and burning the town of Poole. Retiring to Harfleur, they called at Alderney on their way.

- "Il y avait là beaucoup de troupeaux dont les galerès prirent Ie necessaire pour se fournir de viande mais elles ne firent point d'autre mal, parce que les habitants sont pauvres et ne nuiseut à personne, et même ne portent point d'arme."

This gives one the impression of good manners and of humility, but, in view of what follows, it may be safer to construe this passage as the mediaeval figure of speech for a raid, pure and simple.

Winter in Rouen

Contrary winds prevented Nino from again crossing the Channel, and he therefore decided to sail up the Seine and to winter at Rouen. It is interesting to observe that, in spite of the friendly relations with Spain, the good citizens of Rouen were upon their guard when Nino appeared at their gates. The question was debated before Guillaume de Bellengues, Captain of Rouen, and his council, and evidently uneasy in their minds, they decided that the Spaniards should surrender their arms, and should moor their galleys in a certain spot, afterwards known as Le Clos des Galees.

But the somewhat gruff conditions of the authorities of Rouen were not to be of long duration, for Nino was known to many of the French nobles and so soon as his personality was established, he appears to have enjoyed a pleasant time, being invited to stay at the luxurious castles along the Seine.

As might be expected, we soon hear of a love affair, and that, too, with the married daughter of the same M de Bellengues, the Captain of Rouen. She was the young and beautiful wife of a French Admiral, Renaud de Trie. He was very old and sickly, and had retired to end his days at his Chateau de Serifonteine, near Rouen.

Chateau de Serifontaine

Nino, who had recently become a widower, fell in love with the attractive Jeanne de Bellengues. The description in the Victorial of the Chateau de Serifontaine is a complete picture of a great French nobleman's house at the beginning of the 15th Century. It is too long to quote, and I can only hint at the abundance of information of the ordered beauty and quiet of the place; of the chapel with its band of wind instruments and minstrels; of the fine orchards and gardens by the stream; of the lake with its fishes for the castle's supply; of the sporting dogs and horses; of the falcons and their keepers; of the separate lodgings of my lady, joined to the main building by a drawbridge, of the luxurious and dainty furuiture; of the life led by the household, hunting, dancing, and music.

It was into this delightful abode that the old Admiral had invited the sea captain. The Spaniard was welcomed with a banquet, his host doing the honours of his house right courteously, after which there was a ball, when his wife danced for an hour, with the gay Don Nino. The guest then went on a visit to Paris, and can hardly have been surprised, when he returned to Rouen, to learn that the Admiral had been considerate enough to die.

Don Pero hastened to console his widow. But the lovers were unlucky, for Madame l'Amirale might not wed again so soon after her widowhood, while her lover was under orders from the King of Castile. So it was agreed that they should wait for two years, and Pero sailed away towards Harfleur, during an eclipse of the sun, which greatly terrified the sailors.

To anticipate, the end of the story was that the lovers released each other, Nino married Dona Beatrix of the Royal House of Portugal ; while Jeanne de Bellengues took as her second husband, Louis Mallet de Graville, Seigneur de Montaigu. She died in 1419, still in her youth, and lies buried in Rouen Cathedral.

Fleets scour Channel

At Harfleur Nino rejoined Savoisy, and their fleets set out once more to scour the Channel. In the autumn of 1406 the captains separated, and Nino appears to have made the acquaintance of Pierre de Pontbriand, surnamed Hector, a distinguished Breton knight, son of Olivier de Pontbriand, who was one of du Guesclin's captains in the wars in Normandy.

Hector was ecuyer d’écurie of Louis d'Orleans, and had seen much service. Our chronicler also mentions the name of another Breton knight, named Tournemine, almost certainly Pierre, Seigneur de Plancoet, Together they planned tbe expedition against Jersey. To whom belongs the merit of having initiated the enterprise? If we are to believe Gutiere de Gamez, it was entirely due to Nino; but in reading his biography, we cannot get ride of the impression that he constantly seeks to glorify the deeds of his master; and that in so doing, he purposely relegates to a secondary position, those with whom Nino was associated.

We must bear in mind that Nino's forces only consisted of three galleys, and it is scarcely credible that he would have been able to collect of his own initiative, at very short notice, all the troops and vessels which were employed in the expedition. There are many facts which point to Hector de Pontbriand baving been the responsible chief of the French forces, and this is borne out by the documents at the Bibliotheque Nationals, to which I shall refer later.

Attack on Jersey

We may now pass in review the account as given by tbe author of the Victorial. Pero Nino had collected nine whalers of Normandy, and with them was cruising about the coast of Brittany, when he fell upon a fleet of French merchantmen bound for Batz to load cargoes of salt. Nino appears to have induced them to join in the projected attack on Jersey, promising them much booty and a share in the ransoms which would be levied.

They then put into some port on the coast of Brittany, probably St Cast, where Nino met Hector de Pontbriand and Tournemine. Complimentary speeches were exchanged. In two days all was ready, and the expedition, consisting of Bretons, Normans and Castilians, set sail on 7 October 1406, reaching Jersey in the evening during a spell of calm weather.

When night set in, and the tide was high, the troops were landed on the islet where the Priory of St Helier once stood (now occupied by Elizabeth Castle). Gutiere de Diaz describes tbe place with precision, and the mode of attack which had been decided upon by Pero Nino. At daybreak next morning, as the tide receded, the invading force, consisting of about 1,000 archers and crossbowmen, advanced across the sands of St Aubin's Bay to attack the Islanders, who had mustered 3,000 strong, besides 200 horse.

The Jerseymen, according to the chronicle, were commanded by an English Knight, in all probability, Sir John Pykworth, who had just been appointed Keeper in the place of tbe Duke of York, then under arrest. A fierce and bloody combat ensued, which would have ended in a draw, with few left to tell the tale, had not Nino, perceiving a standard bearing the Cross of St George, appealed to Hector de Pontbriand and his men-at-arms. "Amis", he cried, "Tant que ce pennon sera debout, jamais ces Anglais ne se laisseront vaincre; mettons toute notre entente à nous en emparer."

Standard captured

A terrible onslaught ensued; the banner was captured, and the captain of the Jersey corps, who was called the Receiver, was killed. "He died at my feet", relates the chronicler. The Islanders, disconcerted at the loss of their captain, retreated, but the invaders were in no condition to pursue them, and they retired to the Islet to concert measures for renewing the attack on the morrow.

In the meantime, from reconnoitering, and from prisoners, the invaders gathered information concerning the island, its inhabitants and its fortifications. They were told that there existed five castles in the island; the male population numbered between 4,000 and 5,000, the commander was an Englishman, who had led the Jerseymen in the battle, and the survivors had retired to the Castle where there was a town, and whither also their wives, children and valuables had heen sent; finally, that the English fleet then at Plymouth, was expected daily.

The Chronicle bears evidence of some hesitation on the part of the enemy chiefs as to the best course to follow. Nino desired to complete the conquest of the Island and to keep it, but in this he was opposed by the Bretons and Normans, who probably more fully realised the danger of such an occupation if the English fleet put in an appearance.

They were of opinion that, unless they were masters of the Castle of Mont Orgueil, it was a hopeless task to attempt to retain the possession of the island, and they declared in favour of a policy of loot. Nino met their views by deciding that they would advance the following day in the direction of the Castle, and if the Jerseymen did not join issue, a fresh council of war could be held. At daybreak on 8 October they set out, headed by their chiefs mounted on horses captured the day before, and ravaged the countryside.

- "La campagne etait couverte de maisons, de jardins, de moissons et de troupeaux; et tout le pays brulait."

Croix de la Bataille

But on arriving at the heights of Grouville, the enemy found his way barred, and a skirmish took place, at a spot in the immediate vicinity of the present East Arsenal, long known as Croix de la Bataille, a cross having been erected there to commemorate the event. The encounter proved to be as indecisive as the first, upon which an English herald came from the Castle and appealed for mercy, on the grounds that the Islanders were Christians, and that the Queen of Castile was of English birth.

Nino replied by demanding a conference with four or five of the principal inhabitants. They came and said that the Castle yonder was there for their protection, and that it would certainly be defended, but that if money was wanted, they would offer what they could. Finally a ransom of 10,000 gold crowns was agreed upon, of which part was to be paid at once, and four hostages were to be given as security for the balance. A curious stipulation was moreover insisted upon by Nino, that the Jerseymen should pay him an annual tribute of 12 lances, 12 battle axes, 12 bows with their complement of arrows, and 12 trumpets.

The invaders departed the next day with the greater part of the ransom, with their hostages, and with a considerable quantity of booty, principally horses and cows. The Chronicle states tbat they sailed for Brest, where they were received with great rejoicings. Some Breton merchants are said to have taken over the Jersey hostages, and paid the balance for which they were responsible to Nino, who then distributed the money amongst his followers.

Such is the story as related by Gutiere de Diaz. Nino short after returned to Castile and lived till 1450.

French judgments

We have now to examine another source of information, consisting of two arrets (or judgments) of the Parlement de Paris, to be found in the Bibliotheque Nationale, which, while confirming in the main the account in the Victorial, supply us with more precise details and tend to unravely the mystery surrounding the various actors in this adventure.

The first is a judgment rendered on 9 March 1407 upon an action brought by Robert de la Reuse dit Ie Borgne, Captain of St Malo, against Pierre de Pontbriand, surnamed Rector, Raoul du Boul, Guillaume Ie Boucher, Robin des Camps, and Jean Morard, of Harfleur, defendants.

The Captain of St Malo sets forth in his petition, that on 9 October 1406, a certain Jacques Devinter arrived at St Malo from Jersey. The port officials went on board his vessel to examine his papers, to ascertain his nationality, and whether he had the necessary safe conduct to enter the port, as St Malo at that period belonged to the King of France, then at war with England.

Devinter, not producing any safe conduct, was arrested. Then Raoul du Boul, Guillaume Le Boucher and Robin des Camps came upon the scene, and forcibly released Devinter, whom they conducted to Hector de Pontbriand, who refused to surrender Devinter. Upon which the Captain of St Malo obtained a judicial order for his surrender. De Pontbriand not having complied with this order, the Captain of St Malo now sought for a final order to compel him to do so, or pay a sum of 10,000 livres as compensation.

Jersey pirates

The plea put in by the defendants is interesting. De Pontbriand, it is averred, was a good and valiant knight, who had loyally served the King in all his wars. During the year 1406 many rich merchantmen had feared to enter the port of St Malo, being unarmed, and Jersey pirates swarming the roadstead. De Pontbriand had gone to their aid with his fleet and army, and convoyed them safely to Harfleur.

In that port De Pontbriand found a great number of well-armed vessels, and having enlisted the co-operation of a Spaniard named Pero Nino, and of many others, he embarked upon an expedition against Jersey, having first obtained the King's permission. There was at that time in Jersey, a number of Frenchmen, detained as prisoners, who had been captured through the negligence of the Captain of St Malo.

De Pontbriand and his army had landed in Jersey and forced the Islanders to come to an arrangement, whereby they were to pay a ransom of 8,000 livres and to surrender all the subjects of the King of France, whom they held as prisoners.

The Jerseymen had paid a part of this ransom, had delivered up 30 French prisoners, and had agreed to give hostages and security for the execution of this compact. In compliance with these conditions, the Islanders had sent to St Malo with a feeble escort of ships, Jacques Devinter, accompanied by the hostages, all of whom were unarmed, but were provided with a safe conduct from de Pontbriand.

On their arrival at St Malo, Robert de la Hense, the Captain arrested Devinter. The latter succeeded, however, in escaping, and got to Harfleur, but the rest of the crews (not the hostages - observe), were thrown into the dungeons of the prison, and attempts had been made to extort from them heavy ransoms.

Threat to prisoners

Such proceedings, the plea avers, had raised the indignation of the inhabitants of Jersey, who declared that the subjects of the King of France could not be trusted, and it was not unlikely that such conduct would endanger the lives of those French prisoners who were still retained in Jersey.

The Captain of St Malo pleaded that while it was perfectly true that Hector de Pontbriand had acted courageously in a very laudable enterprise, yet he bad not been altogether prudent. The King alone could grant a safe conduct between belligerents. The King alone could organise expeditions against his enemies. No subject had a right to make war without the royal license or a special order from the King's Council. De Pontbriand had not offered any proof that he was so authorised.

And even if it were true that he had obtained the King's permission for this attack on Jersey, in the event of his taking prisoners of war, they could not enter the kingdom without the safe conduct, either of the king, or of some other competent authority. De Pontbriand was not a competent authority, and if Devinter had been provided with a safe conduct from him, it could only be binding as regards De Pontbriand and his own associates.

The defendants, in their rejoinder, argued that they were not obliged to be provided with formal letters to justify the permission obtained from the King in a maner of urgency, as they could prove the granting of it by the evidence of persons worthy of credence. As regards safe conduct, that was undoubtedly tbe King's prerogative, but only in the sense that he alone could grant safe conducts to move about any part of the Kingdom.

The Court thereupon decided that Hector de Pontbriand should give security in the sum of 500 livres tournois, and ordered the Captain of St Malo to set at liberty the five prisoners with their chattels. It adjourned the further hearing of the case, in order that witnesses might be called.

Finally, after witnesses had been heard. Hector de Pontbriand and his adherents were discharged from the action, and Robert de la Hense was condemned to the costs,

De Pontbriand dominant

This document proves the dominant role of Hector de Pontbriand in the attack on Jersey. The judgment, given entirely in his favour, shows his position clearly. In the events which followed the attack, he alone assumes all the responsibility.

The variations or discrepancies in these accounts are not inexplicable, nor have they much importance. The difference of two thousand crowns in the amount of the ransom as given in the Victorial may possibly be explained as representing Pero Nino's share.

As regards the hostages, which the Victorial states were landed at Brest, this difficulty disappears when we remember that the judgment just cited does not state that the hostages were taken prisoners, but that only the sailors and their ships were arrested. When Devinter was rescued, he must have been taken on board one of the whalers of Harfleur, probably La Sirene, commanded by Guillaume Le Boucher and Jean Morart, who accompanied the hostages in Devinter's ship, as the agents of de Pontbriand, and the vessel probably made off for Brest, to join the chiefs, while the emissaries of the Captain of St Malo were busy arresting the inoffensive Jersey crews.

Second judgment

The other judgment of the Parlement de Paris, which we have mentioned, is dated 11 April 1409, and relates to the distribution of the ransom between the Breton and Norman sailors, It is a judgment ordering the registration of an agreement between Hector de Pontbriand and the six whalers of Harfleur.

The names of the captains of the vessels are: Robin Loti, Guillaume Le Boucher, Jean Morard, Geoffroy Boulart, Samson Bart dit Pinte, and Perrotin de Bayonne. They were associated in the defence of Harfleur and the coast of Normandy, with the famous sea captain Robert de Braquemont, who had at one time been an Admiral of Castille and thus represented the alliance between France and that country. His association with those who took part in the Jersey expedition explains the reference in the ‘’Victorial’’ to the co-operation of several Norman nobles with Hector de Pontbriand.

But to return to the ransom dispute. The corsairs of Harfleur were to receive 2,000 livres, and de Pontbriand had signed a bond for this amount in their favour, upon which he had paid a few instalments. When they claimed the balance, he claimed to make a set-off of some porbion of the costs incurred in the action brought by the Captain of St Malo. The court, with the consent of the parties, arranged for a settlement within six weeks.

The parties were in the meantime to attempt to come to some arrangement as regards this set-off, and if they failed, two of the King's Councillors were to decide the question.

And here this episode closes. The scenes of violence and spoliation to which the inhabitants of these islands were exposed during the Hundred Years War, must have been terrible. If we could trace with any precision of details the numberless attacks to which they were subjected in those times, we would obtain a fairly complete picture of the naval warfare between France and England in the great fight for the supremacy of the sea, and assuredly, many a fresh glimpse or its strenuous nature.

Froissart and other contemporary chroniclers do not draw for us as clear and graphic a picture as we could wish of naval warfare, for the very good reason that they were not eye-witnesses of the incidents they relate. The Victorial is an exception, for its author followed his hero wherever he went throughout his long career on sea and land, and it is this which gives value to his fascinating narrative.