It is not surprising that many of the early newspapers did not have very long lives, and that titles were closed down, relaunched with similar names or amalgamated quite frequently.

England

Pamphlets and publications which appeared more regularly and were initially known as news periodicals began to emerge in England in the 17th century and by the 1720s there were 12 London newspapers and 24 provincial papers.

But Jersey did not even have a printing press until 1784 when Jerseyman Mathieu Alexandre, who had gone to England to learn the art of printing, returned to the island with a hand-operated flat press which he installed in his house in St Aubin.

Feeling were running high over the control which Lieut-Bailiff William Charles Lempriere and his supporters among the Jurats of the Royal Court held over the island, reinforced by the political party which had been formed and named Charlots after Lempriere’s father and predecessor as Lieut-Bailiff, Charles Lempriere.

The opposing Jeannots, as the followers of the Lemprieres’ bitter opponent Jean Dumaresq were known, seized on the opportunity provided by Alexandre’s press and Dumaresq and his brother Philippe found the money to set him up as a political pamphleteer.

Monthly journal

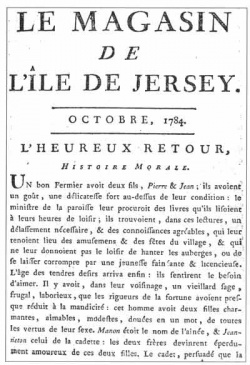

Le Magasin de l’Ile de Jersey, as his first monthly journal was called – French was still the predominant language for those who were educated and could read – was an unashamed mouthpiece for the Magots, as the Jeannots had become known, and did not hesitate to attack Lempriere and his party, either directly or in thinly disguised, potentially libellous accounts of events in an imaginary island called Yeseri.

The publication was an instant hit, and copies were passed from one household to another. Lempriere responded by having Alexandre arrested on a charge of libel. Although there was a long delay and the case never came to court, Alexandre was forced to close Le Magasin.

Weekly Gazette

But he soon responded by launching the island’s first true newspaper in 1786 – the weekly Gazette de l’Ile de Jersey, which featured reports of the Royal Court and the States leaked by Dumaresq and his supporters, and editorials attacking the Charlots.

The influence of the Gazette was enormous and over 11 years under Alexandre’s control, it saw the total demise of the Charlots as a force of influence in island politics. Even before the Gazette started the Jurats’ bench was moving against the Charlots. Lempriere’s father’s arch enemy Nicholas Fiott was elected in 1782 and by 1790 Dumaresq had a majority in the Court and the States. In that year Lempriere died, and it would be another two years before the Charlots finally responded with the launch of the Soleil de l’Ile de Jersey in 1792. But although it outlived the Gazette by a year, the damage had already been done and the balance of power in Jersey had truly shifted.

George Balleine wrote of the Gazette in his History of Jersey and completely ignored the Soleil:

- ”Its party spirit was incredible. It gave entirely one-sided accounts of the private meetings of the States and it harried Lempriere without mercy. This gave a very great advantage to Dumaresq and his party. In 1788 Lempriere complained to the King in Council of the ‘incendiary harangues and publications of evil-disposed persons … this venom is spread over the whole island and artfully directed at the feelings and passions of the multitude, by means of a printed weekly paper called the Jersey Gazette … the inflammatory and artful insinuations are daily sounded in the ears of the undiscerning multitude against Your Majesty’s civil government’. He claimed that it had become impractical to administer justice without risk of insurrection.”

There is no evidence that, even if the Privy Council had any sympathy for Lempriere, it was prepared to do anything to help him with his struggle against the ‘fourth estate’.

Town Hill dinner

Balleine continues:

- ”Political feeling became more and more bitter as the ding-dong battle was waged in the States, in the Gazette and in the stream of petitions to the Council. Dumaresq was now the idol of his party. The Gazette describes a dinner given him in 1787: A tent was erected on the Town Hill and magnificently decorated to receive this patriot guest. Flags floated everywhere, and everything testified to the joy which the presence of Mr Dumaresq instilled into every heart. Two hundred people sat down and, after dinner, Dumaresq was chaired through the town.

Without a sympathetic newspaper to hit back in, Lempriere again complained to the Privy Council:

- ”A mob the the numer of some thousands was invited and assembled by the firing of guns, and exhibited a scene of the greatest riot and disorder; in the evening the party, attended by the populace, paraded in the most tumultuous manner in the streets of St Helier wearing in their hats blue cockades with the inscription of ‘Dumaresq and Liberty’, the said Dumaresq being seated in a chair and carried in the midst of them upon their shoulders with colours flying and music playing; and we are sorry to observe that on this occasion two Jurats and several of the clergy and Constables were among the most active in the crowd.’”

The Charlots would get no help from the Privy Council and their own islanders had clearly turned against them. The turn of the century saw the end of an era in island politics and island publishing.