Emigration

The story of Snowdon Malzard is doubly interesting in that, apart from his military service during the Great War, he was one of the many young migrants who, before the Great War, had left the Island of Jersey for pastures new, or in his case, the vast plains of Canada, attracted by advertisements that carried the offer of free passage and land in the western provinces.

While he was busy forging a new life for himself, war was declared.

He was born on 28 November 1888, the son of Gordon and Rebecca Malzard, of Prospect House, Mont Fallu, St Peter. He featured in Jersey’s censuses for 1891 and 1901, but by the next census, he had left the family home. He had left Jersey for England on the mailboat with five others, Reg AJ Boullier, John C Nicolle, Stanley E Le Brocq, and brothers, Edward A and Charles A Remon, towards the end of January, 1905.

After disembarking, the party were soon heading northwards to Liverpool, from there to embark on the Canadian Pacific Railway’s ss Lake Manitoba. Departing on 24 January, the ship headed to St John in New Brunswick, where the snow covered landscape would have been considerably different to that which they were all too familiar with back in Jersey.

Having spent a week or more at sea in rough seas, dodging the odd ice floe or iceberg, they would now have to endure a railway journey with CPR that whisked them further westward to Vancouver. In just three weeks or so, Snowdon and his fellow travellers had covered more than 5,000 miles.

Undoubtedly the conditions that immigrants were to face in the early days and months in this new environment would prove tough. But, at 160 acres, those parcels of land provided by the Canadian Government were far larger than they might ever have in Jersey. But, in the case of the Remons, both were back in the Island when the 1911 Census was taken. Stanley Le Brocq served with the South Staffordshire Regiment during the War.

Enlistment

Of Reg Boullier and John Nicolle nothing further has been found. But, given that he later enlisted in Canada, Snowdon Malzard clearly managed to make a living, and even found the time to serve with the 6th Duke of Connaught’s Own Rifles, one of the units that formed Canada’s Militia. He volunteered, and enlisted in the Canadian Army on 15 March 1915, at New Westminster in British Columbia, and with his prior Militia service recognised, he was given the rank of Lance Corporal.

He was to be a member of the 47th Battalion, but on 4 June he transferred to the 30th Battalion, which was based at Shorncliffe Camp in Kent. He transferred again to the 7th Battalion on 28 August, while being sent to catch the next troop transport sailing to Boulogne-sur-Mer.

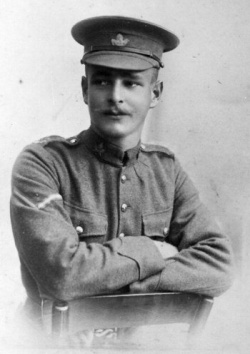

There is little to note from his service record from his arrival with the 7th Battalion until 4 April 1916. He had his pay, travel documents and a leave pass for nine days in his pocket, and was soon heading off to England, and from there he would catch the next mailboat to Jersey. It appears that this was the first time back in the Island since his departure in 1904. His photograph, a Lance Corporal’s stripe prominent, was taken in Jersey by Joseph D Tynan at 41 Bath Street.

Promotions

On 7 June he was promoted Corporal, followed some seven weeks later to Sergeant, on 27 July. Circumstances now changed. On 12-15 August the 7 Battalion marched out of the Ypres Salient and into France, where they reached Eperlecques with, it was noted, very few cases of sore feet. At Eperlecques, over the next eleven days, they underwent further training, including assaults, and a good indication that they were heading to the Somme. In the early hours of the 28th the Battalion entrained at Arques, and via a route that took in Etaples and Abbeville, reached Candas, where they got off and marched to billets, an exercise that was repeated for a few more days until they reached their billets at Albert on 2 September.

On the 7th the Battalion moved up to the front line a few miles north of Albert. The War Diary entry for this day states: ‘Bright and warm. Bn moved to front line and took over from 14th Bn. In an awkward situation. Lt Walker wounded. Certain officers and ORs left in Albert’. The following day the Battalion’s situation warmed up, metaphorically as well as meteorologically, for the War Diary recorded: ‘Numerous casualties owing to gap exposing flank. Gap filled and consolidated. Major Casey and Lt Worsey killed and Lt Mogg wounded. Fine’.

Wounded in action

It was on this day that Snowdon received a wound, in the shape of a rifle bullet, and contusions to his head. The War Diary entry is very sketchy as to what actually occurred, but it does suggest that the Battalion’s position was exposed to enfilading fire, and that the job of dealing with the Germans was given to one company, possibly two. As a Sergeant, Snowdon would have been out in front encouraging the men in his platoon to go forward. Seriously wounded, he was sent back for medical attention. On 13 September he was admitted to the Wharncliffe War Hospital on the outskirts of Sheffield.

The intervening five days included him being operated on at 22 General Hospital, at Camiers, where the offending bullet was removed, to ensure that his condition was sufficiently stable to be evacuated by sea and then undertake the lengthy train journey north. A further operation to examine the cleanliness of the wound took place at Wharncliffe, and this proved satisfactory, his hospital notes indicating that it was both clean and, later, that it had ‘healed rapidly. He was transferred to the Canadian Convalescent Hospital, at Hillingdon House in Uxbridge, on 13 October.

Recovery continued, and from the middle of November he was employed in the Hospital’s post Office. On 10 January 1917, he started to complain of bell-ringing noises in one ear and of recurrent attacks of giddiness and difficulty in walking in the dark. He was now transferred to the Canadian Ear and Eyes Hospital at West Cliff in Folkestone, where he was diagnosed as having concussion deafness, and was kept in for treatment and further tests. He contracted scarlet fever, and was held in isolation for six weeks. He was discharged from hospital on 5 April with the medical Category AIII which was assigned to ‘Returned Expeditionary Force men who should be AI once ‘hardened’’.

Further promotion

He was again at Shorncliffe Camp, on the strength of the 1st Reserve Battalion, but through most of July he attended a course at Seaford, at that time the Regimental Headquarters of the British Columbia Regiment. At the beginning of August he was promoted Company Sergeant Major, and on 2 December he was posted back to the 7th Battalion. The Battalion’s Orders on 14 December noted his arrival and assignment to No 3 Company.

From this point on the Battalion’s War Diary began to contain lengthier daily entries. Much of the Battalion’s time between the beginning of January and the end of July 1918 was spent in and out of the trenches in the Loos sector, although there was a brief spell at Dainville and in the tunnels at Arras in April. The Battalion incurred daily casualties while in the trenches. Officer movements going on leave, being posted or attached were religiously recorded as was the notification of gallantry awards to all ranks. At the end of February, Snowdon Malzard was promoted to the rank of Warrant Officer Class 1, and appointed to become 7th Battalion’s Regimental Sergeant Major, a role that saw him responsible for the men’s turnout, cleanliness, drill, training, and above all, discipline.

On 7 August, the Canadian Corps were moved, in considerable secrecy, to the frontline in front of Amiens . The following morning, they, the 7th Battalion among them, now advanced. From this point on, the Battalion was regularly engaged as the Allied Armies advanced, and casualties rose. A successful assault on 2 September saw the capture of some 600-700 Germans, and many others undoubtedly killed. The Battalion’s casualty figures for this action totalled 127, of which 25 were killed. Throughout the ‘100 Days’ men were still able to take their leave, and Snowdon was in Jersey during October. His return to the front was delayed for about four days, apparently because of disruption to the Islands’ mailboat services, as ships were diverted to carry supplies to maintain the impetus of the Armies’ advance in France.

Then the Armistice was declared. The Battalion had been out of the line since 18 October, and was lodged at Auberchicourt. It now steadily advanced into Germany as part of the British Army of the Rhine, and reached Overath, some 15 miles east of Cologne, before returning to Vaux-et-Borset in Belgium, where it started to shed men for repatriation to Canada and their subsequent demobilisation. The War Diary was closed on 28 February 1919.

Return to Canada

Having received a Mention in Despatches to go with the 1914-15 Star, British War and Victory Medals, for his services, Snowdon returned to England on 15 March 1919, and on 10 April he boarded the SS Carmania at Liverpool, bound for Montreal, where he disembarked on 18 April. A week’s train ride to Vancouver followed, and the 25th, 429119 RSM Snowdon Malzard was demobilised from the Canadian Army, was considered to be in good health even allowing for his now healed head injury, and was now able to pick up the strands of the civilian life that he had left behind just over four years previously.

He would have been expected to resume his farming life in Canada, but among the names listed on the SS Scotian’s passenger list of those landed at Liverpool from Montreal on 9 July 1919 Snowdon Malzard was included. He gave his occupation as farmer and his address as Prospect House in Jersey, and indicated that it would be permanent and a return to Canada was not intended. In just two months he had settled his Canadian affairs, disposed of what land he may have owned, and had bought himself a one-way ticket. What had happened?

Death

Snowdon's sister Irene Pontius’s diary entries for 1920 tells the sad story. She was on leave at Prospect House from China at the beginning of the year. It should be noted that Snowdon was known as ‘Sotie’ by his family. The entries are as follows: 1 January: In Jersey. An uneventful day. It poured and blew this afternoon. Mother and Father went for tea at Kath’s; Gordon is recovering well from mumps. One year today since Nan died. 2 January: Lovely day. We ironed. Reb and Ken went to the Larbalastiers. 3 January: Snowdon and Tony have not been well today. Jack came this morning to ask about Sotie. 4 January: Sotie no better this evening. We went for the doctor who says pleurisy is the trouble. 5 January: A very miserable day. Poor old Sotie is very seriously ill. The doctor fears pneumonia. Tonight at 8.30 a nurse arrived for Sotie. 6 January: Sotie had a bad night but was a little better this morning. This afternoon he was much worse. Tonight we had to send for the doctor again. We were all nearly heart broken when he said there was very little hope. 7 January: After a ghastly night for us all, Sotie died this morning at 7.30. We are all heartbroken at our loss and feel we never can go on again. It is all so sad. We shall miss him terribly. A ghastly day with people in all the time.

As well as being Snowdon’s sister, Irene Pontius was also the grandmother of Suzette Waterhouse, and along with the extracts from Irene’s diary, Suzette recounts that: ‘Actually the rather startling family story passed on to us was that Snowdon died of a broken heart as his Canadian sweetheart was raped by Canadian soldiers (presumably in Canada) and died as a result of this. She is mentioned often in his letters as Harriet, and he names her sisters. The Vancouver forwarding address in the records seems to be her family home. She was Harriet Taynton from Vancouver.