Early memories

During the last 50 or 60 years so many changes have occurred in the life, and outlook of all who have lived during that period, that I feel it would be of interest, not only to the present generation, but to those coming along after we have passed away, for a Jerseyman who has spent the greater part of his life as an active member of this little community, to place on record some of the many experiences in which he has participated, and some of the many changes he has witnessed.

In doing this I am not attempting any orderly detail, although some items stand out in never-forgotten isolation, though they may appear to others as having no apparent logic or intrinsic value. What other people saw and experienced was not always what one lived through oneself.

Neither is this a history of Jersey in the early 20th century. To the student, all that can be available is at the Public Library and in the files of the local newspapers kept there.

What I shall endeavour to set down are my own personal memories, which may be sometimes inaccurate, confused, or even chaotic, though to me they represent a true picture of what happened in those years.

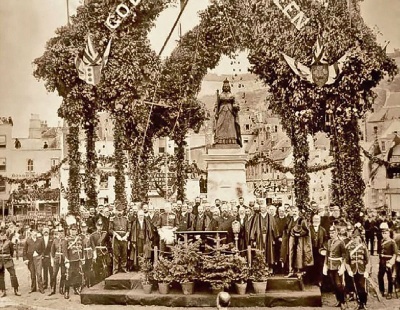

Victoria's statue

The first thing I distinctly recollect was the unveiling of the Queen’s statue in the Weighbridge Gardens. This was in 1887, when, at the age of four, I was taken by my father to witness the ceremony.[1]

My father was a special constable for the occasion, and, placing me in the front row, I stood between two soldiers. One of them quite accidentally, dropped his rifle on my foot, which almost led to a free-fight between my father and the soldier.

Soon after that I was sent to Mr Ollivier’s school in Charing Cross, where Messrs Huelin now have their ironmongery establishment, and I well remember being taken by the master, with several other boys, to see the first incandescent gas lamp.

This had been erected in the Royal Square by the Gas Company, and was a great improvement on the old fish-tail gas burner then in use, which, apart from being highly dangerous, created an amount of soot that quickly spoilt all decorations.

The first gramophone was also on view in the Royal Square, and for two pence you were permitted to place two unsterilised earpieces in position in order to listen to a piece of music played from a cylinder about six inches long, and which sounded much like the sound made by a man singing whilst suffering from a severe attack of nasal catarrh.

But whilst to-day records of that type are out of date and the insanitary method of listening would not be appreciated, in those days we boys thought it “ the last thing in entertainment ”, and every penny we could spare was used, in order to hear the same tune played again, that we had heard several times previously.

Another great source of entertainment in those days was Poole’s Myorama, that generally visited Jersey once a year and gave its “World-Renowned Show” in the Oddfellows’ Hall in Don Street, now occupied by Messrs Tregear.

This show, which principally consisted of the unrolling of large pictures accompanied by appropriate descriptions from the compere, with various hangings of drums, etc, to represent thunder and broadsides of guns from warships, always drew large audiences, and on Saturday afternoons children were admitted for 3d in front seats and 2d in the rear. I well remember the shoving and pushing that ensued immediately the doors opened and the shouting and cheering when an enemy ship was sunk during the course of a showing of the battle of the Tugela River.

We boys were little snobs, and because we were being educated at private schools, were not supposed to mix with boys from the elementary schools and the Ragged School that existed in those Bad Old Days.

This Ragged School was situated in Cannon Street, where are now a number of modern service flats. Many of the children attending this school were poorly clad and ill-fed and I have seen many, even on a cold winter day, going to school in rags and minus boots or stockings.

My mother frequently made the washhouse “copper” into a soup-making vessel, and provided a number of these children with a midday meal of hot soup containing plenty of meat and vegetables. Collections of surplus clothing were made by members of the various churches and chapels for the benefit of these unfortunate little ones.

The Bad Old Days

Although more could be bought with twenty shillings in those days than can be obtained with three times that amount today, wages were terribly inadequate. A good mechanic, plasterer, mason, carpenter or plumber was lucky if he earned 18 shillings or 20 shillings, for a week of 59 hours, and a labourer was rarely paid more than 12 shillings or 14 shillings for the same week. Work began at 7 am and finished at 6 pm, excepting on Saturday when knock-off time was 5 pm.

Apprentices started work at one shilling a week, and the lucky ones gradually increased that to four shillings a week during their fourth year.

The majority of working-class families lived in one or two rooms without indoor sanitation and with a pump outside the house from which water was obtained for washing and cooking, etc. Some families, and I emphasise some, had a weekly bath-night, when water was heated in the washhouse copper, and then poured into the washtub. One filling had to do for at least two grown-ups or three or four children. The modern porcelain bath with piped water was almost unknown, except in the houses of very wealthy people.

Rent and food were remarkably cheap, if measured by 1954 standards. Bread was 5½ d. for a four-pound loaf, eggs were 6d, 7d and 9d per dozen, butter 1s 6d and 1s 8d per lb, and potatoes six pounds for 2½d. A pig’s head for making into brawn could be bought for 21/2d per lb, and conger for 1d per lb.

But even at those prices the lot of a working man with a family was a hard one; and many went in dread of even a few days illness, or a week or so of unemployment, for on their small wages little or nothing could be saved for the proverbial ‘rainy day’.

The great ambition of many families was to have a special suit or dress for Sundays, and great care was taken of these. Children wore them to attend Sunday school, had to change them immediately on return home, and change into them again if taken out by their parents on a Sunday afternoon or to Church or Chapel on Sunday evening. The majority of people were Church or Chapel members ; and large congregations attended both morning and evening Sunday services, plus a prayer-meeting on Fridays.

One of many inducements to attend Sunday school was the annual Sunday school treat, when the children, accompanied by their teachers and some of the parents, were taken into the country in charabancs and vans. Sports were then held, prizes distributed to the winners of the various events, and a bumper tea provided. The drive home in the darkness was often the beginning of a romance that years afterwards meant a courtship and marriage for those who had first met at a Sunday school treat. I have known of many such.

Another great day was the Sunday school anniversary. Great preparations were made for this event, at which hymns were sung by specially-trained children’s choirs, the lessons read by one or two of the senior scholars, and a sermon preached by the minister specially for children.

On the following Monday or Tuesday came the prizegiving day. Every boy and girl who had made a regular attendance at Sunday school received a prize. These prizes principally consisted of Bibles or the ‘’Pilgrim’s Progress’’, with now and again something of a less religious type, but never of the type boys and girls read today.

Some of the Sunday services in those days lasted for from two to two-and-a-half hours, with the sermon taking half the time. The story of Adam and Eve and the condemnation of the wicked to everlasting Hellfire were consistently preached and accepted literally, and illustrated books depicting the wicked being prodded with pitchforks into raging furnaces were considered quite the thing to show to children in order to induce them to be good little boys and girls.

The Newfoundland Trade

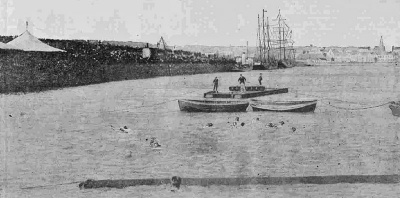

One of my earliest recollections is that of frequent visits to the harbour to see the ships being made ready for their annual visit to Newfoundland for the cod fisheries.

As a general rule these wooden ships left Jersey at the end of March, or the beginning of April, and returned during October or November. In the winter months they filled what was termed the Old Harbour, the harbour in front of what is now named Commercial Buildings. The scene in those days was one of great activity, dozens of carpenters, shipwrights, sail makers and smiths being employed preparing the ships for the next season’s voyage.

Almost every store along Commercial Buildings contained businesses engaged in industry connected with shipbuilding, ship repairs and revictualling. A large wooden dry-dock was moored alongside the quay and ships were placed in it one after another for repairs to their hulls, and the tapping of the hammers wielded by the shipwrights caulking the seams with tarred hemp could be heard continuously.

Just before leaving for their voyage the placing of foodstuffs on board took place. Barrels of salt pork and huge tins of ship’s biscuits were the principal items, and large tanks of fresh water were also carried. I well remember a bakery at the bottom of Pier Road that supplied most of the ships’ biscuits and where bakers worked night and day for some weeks previous to the departure of the ships.

These biscuits were about six inches in diameter and about an inch thick, all right if soaked in hot milk, as I have often had them for breakfast, but eaten as they had to be on the voyage, only soaked in hot water, and often flavoured by myriads of weevils, they can hardly, by any stretch of the imagination, have been even slightly appetising.

But men were more easily satisfied in those days, and hundreds went year after year, knowing full well before they went of the hard life facing them, including very often a voyage to the fishing grounds of 50 to 90 days, with small pay, poor food, poor accommodation and some months of dangerous and hard work on the Newfoundland Banks, before returning for a few months to their native land.

Many failed to return, for almost annually returning ships brought news of accidents whilst fishing, of men who had decided to settle down in the new land, or of shipwrecks with the loss, in some cases, of all on board.

Gradually, fewer and fewer ships were engaged in this industry and eventually none remained. The old harbour became deserted, the stores changed over to potato and tomato stores, the old dry-dock was broken up and part of the harbour filled up to make what is now a parking place for cars, unthought-of of in the days of the wooden ships. To see the ships go out in the early spring was an experience never to be forgotten.

The sailors were paid a month or two’s wages previous to sailing, presumably to provide their families with spare cash during their absence. Many of them spent a good deal of those wages on having a good old drinking bout the day before sailing, and many had to be taken down to their ships on a police truck and placed on board.

The ships were taken by a tug out into the roads behind Elizabeth Castle, and we boys often manned the capstan, that until quite recently was at the end of the Albert Pier, in order to assist the ships proceeding out of the harbourmouth. The apprentices on the ships did their best to assist the skipper whilst the seamen recovered from the effects of their carousal.

Swimming

The annual swimming matches of the Jersey Swimming Club were held in those days in the Harbour. The Albert Pier was lined with marquees and seats for the spectators, and barges were moored for the use of officials and competitors. I well remember, inasmuch as I was a competitor, when the English champion Tyers came to Jersey and used, for the first time locally, the Trudgeon, two-arm overhand stroke.

Radmilovic, the Welsh and English champion also made an appearance and competed in, and won, the two races in which he took part. This was considered one of the annual red-letter days and the event was always well patronised. Another important annual event was the Cycling Club’s Annual Gala that took place at the Cycling Track that existed where are now the Florence Boot Houses at Greve d’Azette. English champion cyclists always crossed over for this event and on several occasions the whole of the local spectators were thrilled to see our local champion secure the victory from the visiting champions. Apart from the racing cycles similar to those of today there were events for the penny-farthing and tricycle machines.

The track was well banked and was an ideal place for these events, and the pity is that for financial reasons it eventually was demolished and sold.

Notes and references

- ↑ The writer’s memory failed him here. The statue was unveiled on 3 September 1890, when he was eight years old