The 'island site'

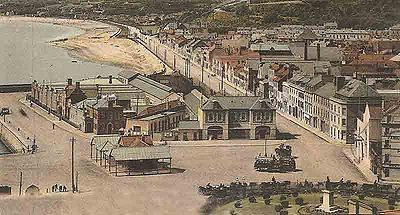

An early 20th century tinted photograph of the Weighbridge area and 'island site'

The original article was accompanied by a number of drawings and plans which are not suitable for website reproduction. They have been omitted and the text adjusted where necessary

|

Introduction

In the autumn of 1997 the States Planning and Environment Committee refused permission for a scheme which involved the demolition of many of the buildings on the 'island site', the area on Saint Helier's waterfront between the Esplanade, Route de la Liberation, and Liberation Square. The writer was subsequently commissioned by the committee to review the issues underlying their decision, the result being presented to the States in January 1998.

A crucial aspect of the task was to assess the architectural and historic interest of the buildings and structures on the site, both as a whole and in their elements, since while there was general agreement on the value of the ornate perimeter wall, opinions differed as to the value of the interior buildings, many of which formed Jersey's Public Abattoir until 1982. This paper is based on that assessment, its arrangement betraying its origin.

As reclaimed land, the whole Island Site was originally in States ownership, and mostly has remained so, subject to leases. The majority of the surviving buildings were indeed commissioned by the States, and in most cases the original contract drawings (and many others) remain in the archives of the Public Services Committee. Those drawings, coupled with physical analysis of the extant structures, enabled the sequence of construction and the uses of the buildings on the site to be established. No attempt was made to undertake a comprehensive study of all archival and secondary sources; rather, research was directed to answering particular questions which emerged.

The Island Site, particularly the southern half including the abattoirs, has been the subject of incremental development and change over more than 150 years. In common with many industrial sites, it has produced a relatively fine-grained palimpsest of historic buildings and spaces, with a complexity and diversity of form and construction which normally take much longer to develop in non-industrial historic areas. The result is a distinctive sense of place and of historical continuity.

Evolution of the site

The sea wall, slaughterhouse and market c1829-35

Between 1829 and 1835 a new sea wall was built forward of the earlier shore line of Saint Helier, thus formalising the quayside as the Esplanade, and giving rise to yards and warehouse development between the new quay and Commercial Street behind. About half way across what is now the north side of the Island Site, the sea wall turned south-eastwards.

The cattle market had for many years been near this general location on the foreshore, but it was then formalised on the triangular site between the Esplanade and the sea wall, separated by a narrow cobbled lane (recently called Les Ecuries du Port) from the slaughterhouses, a single-storey block whose rear wall was formed by an upward extension of the sea wall.

Nothing of the old market now survives, other than part of its plan still being defined by later buildings; the last remnant appears to have been removed around 1913. But a remarkable survival is the southern part of both the lane and the original slaughterhouses, consisting of a row of single rooms, each with a door and window in granite rubble walls, under a massively constructed flat roof against the sea wall. These compartments were, to judge from the current name of the lane, later used as stables, and now serve a variety of purposes.

Harbour extension and new Harbour Office c1847-63

The quayside was extended south-westwards by infilling forward of the earlier wall, to a new wall to the south of the Island Site, which formed the end of the new harbour, enclosed on the west by Albert Pier. This work began in 1847 and was completed in 1853.

The new Harbour Office was built in 1863 at the south-east corner of the Island Site, to the design of Thomas Gallichan, and is a finely detailed two-storey granite building. Whilst handsome, it was clearly more so when it had a cornice and blocking course rather than the present eaves gutters.

By 1867, the abattoir buildings had been extended by a north-south range, returning eastwards to enclose a yard. More detail comes from a photograph and a plan in the States archives showing the situation just before the lease of the railway lands in 1869. By this time there was a modest house for the Inspector of Cattle (or foreign meat), and buildings including the old slaughterhouse were already extant, although as will be seen, they have been much altered since.

Visually the site was dominated by a covered yard further west, the 'Cattle Depot' or lairage for imported cattle. The western part of the Island Site was divided into primarily storage yards for bulk goods awaiting shipment, including china clay. The plots were 12m (40 ft) wide, and ultimately, at least, became divided by stone walls (shown to be demolished on an 1888 plan).

The Jersey Railway, 1869-70

A railway from Saint Helier to Saint Aubin was built in 1869 -70. The Saint Helier terminus faced what is now Liberation Square, and the train shed, sidings and tracks occupied a wide strip of land across the north side of the Island Site, parallel with the Esplanade, cutting across and obliterating the northern part of the diagonal line of the 1829-35 sea wall and the original slaughterhouses.

The opportunity was also taken to widen the Esplanade to 56 feet between building lines. These works involved greater demolition of the slaughterhouses than some had realised, and the work was temporarily held up after the Clameur de Haro was raised by Jurat de Quetteville.

Little physical evidence of this phase of the site's development now remains. There is a length of the south-west wall of the former train shed, which shows the infilled seatings for the original parabolic laminated timber trusses which covered the platforms in a single clear span. Had they survived, they would have been of considerable interest; but they were replaced in 1893 by a double span of angle iron trusses, the stumps of some of which survive, supported on granite corbels carried on an upward extension of the original wall. A low, panelled, brick and granite rubble wall also survives along the north side of the site, towards the western end; the railway line ran immediately inside it.

A tall granite rubble wall also survives defining the western, triangular yard which appears to have been integral with a railway workshop building which extended further north (probably the 'smithy' on the 1869 plan; its south gable wall alone now survives).

Use of the surviving slaughterhouse west of the Harbour Office now intensified. The predecessor of Albert House, the residence of the Inspector of Foreign Meat, was enlarged.

New abattoir and other developments, 1888-1913

In 1887, the States forbade the slaughtering of cattle anywhere in the Island other than the public slaughterhouses, which inevitably were inadequate to cope. That was the spur for the construction of a new abattoir and depot for imported cattle on the Island Site in 1888 to designs by H G Hammond Spencer, assisted by the States' architect, E Berteau.

Spencer was a resident of Saint Helier, and a civil engineer rather than an architect. After serving his pupilage from 1851 to 1855, he was involved in railway construction in England, France and Luxembourg, and in 1869 -70 on the Transcaucasian Railway, before moving to Jersey as Engineer in Chief of the Jersey Eastern Railway.

He was elected an associate member of the Institution of Civil Engineers in February 1875. In 1879 he had been commissioned, with P S Le Cornu, to report to the States on the inadequacies of the pier recently constructed at Greve de Lecq. He retired to East Grinstead in 1901 and resigned from the Institution in 1905.

New accommodation for pigs followed to the west in 1898 and further work on the abattoir continued in stages until 1907, by which time the buildings had taken almost the form in which they survive today. Ironically, in the previous year prohibitive regulations, introduced in response to outbreaks of disease, were consolidated by the States into an effective ban on the import of live cattle for which so much of the accommodation was intended.

The abattoir buildings were grouped behind an ornate wall of Guernsey stone with Jersey granite dressings; over the gateways are Dutch gables which were a leitmotif of the Queen Anne style. The wall was extended and returned northwards to enclose the open yards to the west and form a screen to the railway sidings and workshops.

Whilst the screen wall was clearly intended to be a major piece of civic architecture, in both its design and in its construction, it is integrated into the buildings and activities behind. In 1900 Albert House was rebuilt to complement the Queen Anne style of the 1888 screen wall, a vigorous composition which makes a considerable contribution to the townscape. The development, form and significance of the abattoir itself is considered in more detail below.

The public face of the Island Site was further enhanced by the construction of a new railway terminus building in 1901, to designs by Adolphus Curry, facing eastwards across what is now Liberation Square. In 1896 the ground floor of the Harbour Office was reconstructed to serve as the Impot Office, and further alterations followed in 1906 to convert it to the Post Office.

But proposals in the same year to link it to the station by a grand facade following the style of the screen wall, with a store shed behind, did not proceed. Instead, in 1913 a small building to the south of the railway station, probably the last surviving trace of the 1830s cattle market, was replaced by the existing two-storied building. This housed a merchants' room on the ground floor and offices above, with a gentlemen's public latrine in the single-storied section to the rear. The latter was lit by an elaborate clerestoried rooflight, like those often used over billiard rooms. The roof over the adjacent section of Les Ecuries du Port probably dates from around the same time.

The single-storey office building constructed of brick against the sea wall north of the Harbour Office was built before 1900 (being shown on a plan of the new Superintendent's house); and indeed, unless it is a replacement of an earlier structure on the same footprint, appears to have been built between 1867 and 1869. It was converted from a store to an office for Impot officials in 1905.

In 1893, the screen wall was extended west from the cattle depot, to enclose a walled store yard (taken into the abattoir in 1898) and a triangular corner site, area 1, which became the Harbourmaster's Yard. A utilitarian two-storied building with a simple queen post truss roof was constructed on the north side, open to the yard at ground level, its south and west walls being carried on steelwork. Single-storey open-sided sheds were built around the remainder of the perimeter of the yard. Soon afterwards, the screen wall was finally extended to the railway line.

The later 20th century

The centre of the triangular yard was covered with a largely glazed roof in 1925, to become the first Powerhouse of the newly-formed Jersey Electricity Company. The Harbourmaster's Yard was displaced to a smaller area to the north. In 1939, the existing small-scale doors and windows were inserted seamlessly into the perimeter wall.

Changes in machinery involved much minor change internally, and, probably post-war, the roofs of 1893 and 1925 were replaced by the extant, utilitarian, concrete and timber decked flat roofs. Until c1963, the ]EC continued to occupy the powerhouse, whose legacy is their substation, built in 1992, the adjacent section of the perimeter wall being reconstructed at the same time.

The railway closed in 1937, following which its land assets were sold to the States. Its rivals, Jersey Motor Transport's coaches, had taken over the former Harbourmaster's Yard as a bus shed as early as 1934, and later expanded onto the railway site, eventually building the undistinguished industrial sheds which are still extant. The train shed, however, survived until after 1977; subsequently, its site became a car park.

A World War II gun emplacement was built at the extreme west corner of the site, behind the end of the ornate boundary wall, to command the Esplanade. The gun port remains, with the reinforced concrete structure behind.

The former terminus building was adapted as the Tourism Office, and extended to the rear, in 1985.

Abattoir development 1888-1907

Seen externally, the perimeter wall consists of three distinct sections: the three gables to the west of Albert House, accommodating roofs returning almost at right angles over covered accommodation for cattle and dated 1888; the more uniform section to the west and north, which enclosed both structures and open spaces, punctuated at irregular intervals by gateways, largely added in 1894 -5 (and in part altered in 1936); and a further section, added in 1900-1901, also with windows, linking Albert House and the Harbour Office.

The plan of the new abattoir developed from the entrance yard to the earlier slaughterhouses and cattle depot, which as we have seen had been developing on the land west of the Harbour Office since the 1860s. The first major phase of new construction in 1888 comprised:

- The covered way running the whole length of the site, under a timber roof with extensive glazing, which was the primary circulation route for the complex, and physically separated the beasts in the lairage from the slaughterhouse itself, in accordance with best practice at the time. It was still entered from the original entrance yard.

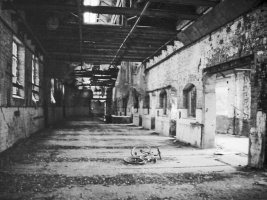

- The lairage or cattle depot for imported livestock, a large area divided by brick arcades into three equal bays, expressed as ornate gables on the quayside (now La Route de la Liberation) frontage, and covered by slated roofs nine bays long, with extensive top lighting. Only the central archways of the arcades originally came down to floor level, providing communication between the bays. The remainder rise from a low plinth, at the level of the tops of troughs (now mostly removed) and tethering rings (most of which survive) for 156 cattle. A further short bay was provided to the east, opening into the yard adjacent to the Superintendent's house, which provided an alternative means of entry. From the large doorways in the centre of the northern wall of each bay, the cattle were led across the covered way into the slaughter hall (figure 1, ]), a tall building with a queen post roof with a continuous louvered ventilator along the ridge, the north side of which was glazed. This was divided by railings (now gone) into ten compartments used by individual butchers, each with a high-cilled window facing north, with two cupboards set high in the wall to each side, floors of granite slabs with gutters, and a window and doorway on the south.

- The yard, with a gateway in the south wall, enclosed on the east and west sides by unpierced fair-faced granite walls. Against the east wall were four sheep pens, a sheep yard, and the manure pit. The southern pen was replaced a few years later by a pay office.

Newspaper report

The result was described in glowing terms on its opening on 17 August, 1889, by the Jersey Times and British Press:

- ”Our New Depot and Slaughterhouses are on a par with the importance and imperative attention which this trade merits, and will compare more than favourably with those of many larger towns. Nothing seems to have been omitted, and favourable opinions have been everywhere expressed as to the manner in which the work has been executed. Constructed in little over twelve months and at a cost of between £4,000 to £5,000 they are a thoroughly satisfactory piece of work, and all concerned may well be congratulated.

In 1898, a further walled Store Yard to the west was brought into the abattoir site and new piggeries, built behind the screen wall which had been extended in 1894. The piggeries consisted of lean-to brick buildings flanking a central covered way with an iron-framed roof supported on cast iron columns. The upper parts of both pitches of the high roof were glazed, the lower parts and the lean-to roofs slated. Each of the six bays provided accommodation for eight pigs, entered via a central door flanked by sash windows. There was some accommodation for calves at the north end on the east side, and a boiler house opposite. The covered way and slaughterhouse were also extended westwards by three bays to provide a slaughterhouse for pigs.

This phase is of particular interest for the quality and elaborate detailing of the construction. The openings in the walls are formed with bullnose bricks, whilst the cast-iron columns built into the walls have Corinthian capitals and support surprisingly decorative iron trusses. The columns even have cast-on flanges under which the slates fit, at exactly the pitch of the roofs. That these details were intended, rather than the columns being left over from some grander purpose, is confirmed by the contract drawing.

In 1892, the southern part of the entrance yard was covered over, using roofs of the same style as over the lairage, the trusses carried on brick piers rising from the eaves of the adjacent single-storey buildings, to allow cross ventilation.

House rebuilt

In 1900-01, there was a major phase of work, involving the rebuilding of the Cattle Inspector's House which survives essentially in its original form save for the loss of a greenhouse at first floor level above the scullery (the scars of its roof are still visible on the gables). At the same time, the screen wall was completed by eastward extension to the Harbour Office. Behind it, what was evidently a pre-existing single¬storey building was reconstructed to provide an office with a new ventilated meat store behind. For the first time, a concrete roof supported on steel joists was used. The three ventilator openings, though blocked, are still traceable in the east wall, as well as a blocked opening in the north wall.

The 1901 plans had suggested that the store was 'suitable for refrigerating chamber', but refrigeration first appears in 1903, when the old slaughterhouse facing the entrance yard (until then used for slaughtering local cattle) was converted to a chill room, with its plant at the northern end. Soon afterwards, the 1901 meat store and store were converted to chill rooms, with an engine house between them, formed by building a wall on the east and roofing over the resultant space.

Some time later the old slaughterhouse lost its refrigeration plant, and was converted to a meat inspection room. The pitched roof was replaced by a flat concrete one similar to the meat store opposite, but incorporating north lights.

In 1907, the entrance yard roof was extended northwards to cover the whole area up to the flank wall of the trainshed. At the same time, building B was truncated, and the existing brick archway through the north end of the surviving part of the sea wall formed.

The introduction of refrigeration, coupled with the effective ban on the import of live cattle from 1906, made the extensive lairage redundant for its original purpose, and it was adapted to quarantine kennels and stores. By 1933 there was already a JEC substation in the south-west corner of the piggeries, and works to appropriate most of the west side were about to begin. However, the slaughterhouse itself continued essentially in its 1907 form until a new slaughterhouse was opened at La Collette in 1982.

Discussion

The abattoir buildings are notable not only for their Queen Anne frontage to the quay, but also their generally well-crafted and well-proportioned interior spaces in the functional tradition, yet with particularly elegant roof structures of a greater variety (and in one case, richness of detail) than is normally found in industrial buildings. The buildings surviving on the site to the west are by contrast wholly utilitarian. This section attempts to suggest why this difference arose, by considering the context in which the abattoir was conceived.

Origins of public abattoirs

The slaughter of animals was, historically, undertaken by butchers near the point of consumption since, before refrigeration, the principal means of keeping meat fit to eat was to keep it alive. The alternatives were smoking and salting, which produced a rather different product. Beasts were typically killed by butchers in small buildings attached to the back of their shops, or similar rooms in farm or estate buildings.

In the 19th century, there was an increasing tendency throughout Europe to regulate such small-scale enterprises, for two reasons: firstly, in densely developed urban areas, they were a major nuisance and health hazard; and, secondly, the absence of supervision allowed diseased and tainted meat to enter the food chain.

Between 1807 and 1818, Napoleon I established five public slaughterhouses in Paris and, in 1810, ordered that public abattoirs should be set up in all large and medium sized towns in France. At Saintes, for example, the small stone slaughterhouse still survives, now housing a collection of Roman sculpture from the city. In or near continental towns, the slaughter of animals only in public abattoirs rapidly became compulsory under the law, and in Germany the buildings tended to become particularly elaborate and numerous, with around 900 by c1930.

Scotland

In the United Kingdom only Scotland followed the continental model. The impetus came primarily from the fact that butchery was already in the hands of 'fleshers corporations', who provided communal abattoirs for use by their members. The Burgh Police Act 1892 consolidated previous legislation to the effect that once a public abattoir was provided, butchers could use no other place in or near the burgh.

In 1851, a large municipal slaughterhouse was built at Fountainbridge in Edinburgh to designs by David Cousin (1809-1878), 'having a plain yet handsome and massive entrance, in the Egyptian style, adorned with great bulls' heads carved in freestone in the coving of the entablature: The architect ‘brought to bear upon them the result of his observations made in the most famous abattoirs of Paris, such as du Reule, de Montmartre, and de Popincourt’.

The site was superseded by a new abattoir at Gorgie in 1908. Glasgow's first municipal slaughterhouse was evidently erected in 1744, but the Hill Street Slaughterhouse of c1909 -10 had effectively taken the place of a variety of earlier establishments by 1914. It was no doubt efficient, but photographs suggest that it was architecturally utilitarian.

In 1935, the Edwardian slaughterhouses of Edinburgh and Glasgow were still considered among the most satisfactory in the United Kingdom; it was ' a matter of great regret that the abattoirs of England and Wales are generally so far behind those of continental countries and even those in Scotland'.

In the rest of the United Kingdom, urban butchers remained antipathetic towards the compulsory use of public abattoirs, regarding them as an inconvenience and a tax on their activities. Slaughtering in the slum alleys and courts of major English towns, such as Leicester, remained common in the inter-war decades, by which time a third objection had emerged, the cruelty to the animals concerned.

England and Wales

Nonetheless, public abattoirs were built in some English and Welsh cities and towns in the 19th century, and increasingly during the early 20th century. By 1928 the Ministry of Health could name 82 such places. Some, like those in Sheffield and Liverpool, were no better than the private slaughterhouses in dank courts, the former consisting of derelict timber sheds. Both were replaced around 1930.

Jersey was clearly more attuned to continental (and Scottish) practice, since public slaughterhouses were provided adjacent to the cattle market from about 1835, although their use was not compulsory.

United Kingdom legislation did, however, lead to the provision of large public abattoirs in ports of entry for imported cattle. The development of steamships from the 1830s opened up the trade in live animals, initially within the United Kingdom (eg from the Scottish Highlands to London) and, following the Free Trade Act of 1842, from Europe.

The European trade peaked in 1864 (1.3 million animals), ironically coinciding with the worst impact, during the 1860s, of epidemics of cattle diseases and the gradual realisation that the imports were primarily to blame for them. Legislation in 1869 allowed the Privy Council to prohibit the importation of cattle from infected countries, save for immediate slaughter; another act, in 1878, required slaughter at the port of entry unless the country of origin, and the stock, could be shown to be free of contagious diseases.

The European trade was finally extinguished through ever tighter control in the 1890s, but the trade in live Irish cattle and, from the 1870s, Canadian cattle and pigs, remained important to the United Kingdom well into the 20th century. This was so despite the beginning of the importation of frozen meat from around 1880.

Development of abattoir buildings

Abattoirs have not so far attracted great interest from architectural historians. Nonetheless, it is possible, from this brief survey, and the development of the Jersey abattoir, to describe their evolution as a building type.

It originated in small, single room slaughterhouses. The statutory lists of protected historic buildings in England include some 80 examples, largely in rural areas, either surviving in recognisable form or identifiable by name ('the old slaughterhouse', etc). Each compartment of the 1835 slaughterhouse is similar to these, but as the first step towards the development of a distinctive building type, in Les Ecuries du Port they were grouped together and treated with a degree of architectural formality.

The next step seems to have been to construct covered stalls for beasts awaiting slaughter, linked directly to each of the individual slaughterhouses; the Ponton Street abattoir in Edinburgh comprised initially eight blocks of buildings of this type, substantially if simply constructed.

Later slaughter halls were constructed as single spaces, with the killing areas less solidly demarcated, and the lairage integrated into a more developed plan. Lairage at abattoirs at points of entry for foreign cattle naturally tended to be more extensive than that at internal sites.

This development of the plan seems to have been happening in the layout of the Saint Helier abattoir extensions of the 1860s (although little physical evidence survives). It was given full and formal expression in the rebuilding begun in 1888, which also included another fundamental innovation in planning, the covered way separating the lairage from the slaughter hall.

Apart from facilitating circulation, the separation caused less alarm to the beasts awaiting slaughter (considered important at the time, primarily because of the adverse effect of distress on the quality of the meat).

Isle of Man

The 1880s saw the construction of large scale municipal slaughterhouses at two other ports of entry, Birkenhead and Douglas, Isle of Man, the subject of competitions won by the Birkenhead architect Thomas W Cubbon in 1885 and 1888 respectively; and a smaller example in Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, dated from 1884.

The abattoir in Birkenhead, begun in 1886, survives, although the architect does not seem to have been Cubbon. It is of red brick with terracotta dressings. Like the Saint Helier example, it presents large ventilated gables to its road frontage, and has a degree of architectural elaboration.

Its plan, too, has similarities, although the covered yards or lairage communicate directly with a slaughter hall set at right angles, itself separated by a covered way from a 'dead meat market' (absent from Saint Helier).

It, too, has a separate pig lairage and slaughterhouse. The building (statutorily listed grade II) is not of the same quality of design or construction as the Saint Helier abattoir, and has been substantially altered, having lost its elaborate entrance gateway around the 1970s.

The Douglas buildings, completed in 1892, were more utilitarian, and have been demolished save for the entrance block. The Haverfordwest buildings, although on a smaller scale than the others, were well detailed in a rustic classical or Italianate manner (wide overhanging eaves, clerestories, Diocletian windows), with two parallel ranges facing each other across a yard, with lairage attached at right angles to one of them, which was clearly a slaughterhouse, undivided by permanent partitions. The buildings were listed grade II in 1986, despite being significantly altered in the 1950s and already derelict, but unfortunately they were demolished in 1991.

Continental comparisons

Whilst, then, some United Kingdom Victorian abattoirs were more than utilitarian in aspects of their design and construction, none made or makes the architectural show of the Saint Helier abattoir, nor was associated with an Inspector's House as an integral part of the plan. The inspiration for these aspects appears to have been continental:

- German abattoirs are often constructed with costly materials and an amount of ornamentation which are not absolutely essential. The slaughtering hall at Straubing, for instance, is faced with white marble. Abattoirs, indeed, are often built in such decorative style that the public slaughterhouse is not infrequently the handsomest building in the town - Macnaghten.

At Barmen, the slaughter halls were vast aisled spaces, cross-vaulted above the clerestory, with elaborate cast iron columns, the whole complex being set in spacious grounds. By contrast, advice in England was that the buildings should be 'simple architecturally because the money is wanted for more practical purposes', chiefly hygiene.

The contrast with both utilitarian industrial buildings on adjacent sites, and with contemporary abattoirs in the United Kingdom, emphasises that the States built the 1888 abattoir to the architectural standards of a Victorian public building, which from the tone of newspaper articles published at the time, it was clearly considered to be.

This reflected contemporary continental practice, and explains the use in the piggeries of ornate cast iron columns and brackets, and carefully chamfered timber purlins and diagonal boarding throughout, in much the same fashion as the Halkett Place Market Hall. As such, it warranted a paragraph in the ‘’Jersey Times and British Press Almanacs’’ of the early 20th century as one of the sights of Saint Helier, in its recommended excursion around the town.

Conclusion

The development of the public abattoir as a specialised historic building type during the 19th century is well demonstrated by the successive buildings still surviving on the Island Site, very little altered in their basic form since they were built. The c1835 and 1888-1907 buildings are of particular interest as historic documents, preserving the original forms, sequence of spaces and many evocative details, which are likely to be a lasting source of interest.

They were designed and constructed to a standard which reflected their public function and status, with well detailed and proportioned spaces which set them apart from contemporary, purely utilitarian industrial buildings. In the circumstances which gave rise to it, and in its standard of design and construction, the Saint Helier abattoir stemmed very much from continental precedent, reflecting a fusion of United Kingdom and continental influences to produce something distinctively of Jersey.